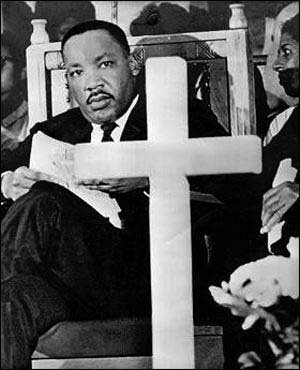

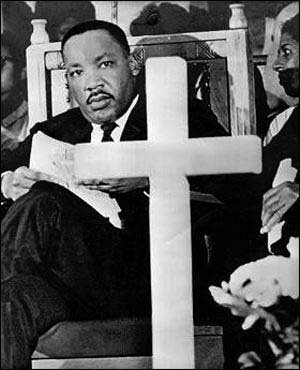

Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, wrote an excellent piece for the New York Times on the need to speak out about Israel-Palestine. Drawing parallels to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s very unpopular stand against the Vietnam War, she argues that we can’t remain silent on the apartheid, discrimination, and violence being perpetrated against the Palestinian people today. We can’t let a preference for order, calmness, or the status quo blind us from seeing injustice and doing something about it.

In this post, I discuss Michelle Alexander’s piece and reflect on a difficult statement of Dr. King’s about white moderates. I then relate this to the teachings of Jesus, which we know inspired and helped form Dr. King’s stance on justice and nonviolence.

Israel, Palestine, and BDS

One of the movements protesting Israel’s treatment of Palestine is known as the BDS movement, which stands for boycott, divest, and sanctions. It draws inspiration from a successful BDS campaign which helped end apartheid in South Africa. Alexander’s piece highlights examples of people who have faced repercussions for boycotting Israel or for simply refusing to sign a statement saying they won’t participate in a boycott of Israel. She highlights that anti-Semitism is still a very real and disturbing problem today, but that opposing policies of the current Israeli government is not in and of itself anti-Semitic. Quoting Alexander’s examples of retribution for the BDS stance:

Bahia Amawi, an American speech pathologist of Palestinian descent, was recently terminated for refusing to sign a contract that contains an anti-boycott pledge stating that she does not, and will not, participate in boycotting the State of Israel. In November, Marc Lamont Hill was fired from CNN for giving a speech in support of Palestinian rights that was grossly misinterpreted as expressing support for violence. The website Canary Mission – which compiles dossiers on Palestinian rights advocates and labels them racists, anti-Semites, and supporters of terrorism – continues to pose a serious threat to student activists.

And just over a week ago, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in Alabama, apparently under pressure mainly from segments of the Jewish community and others, rescinded an honor it bestowed upon the civil rights icon Angela Davis, who has been a vocal critic of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and supports B.D.S.

But that attack backfired. Within 48 hours, academics and activists had mobilized in response. The mayor of Birmingham, Randall Woodfin, as well as the Birmingham School Board and the City Council, expressed outrage at the institute’s decision. The council unanimously passed a resolution in Davis’ honor, and an alternative event is being organized to celebrate her decades-long commitment to liberation for all.

I highlighted in a previous post a Mennonite mathematics teacher who was denied a state contract to help train other math teachers. The reason was that she refused to sign a statement required by Kansas state law saying she wouldn’t participate in BDS. She teamed up with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to sue, and in January 2018 a federal judge overturned the Kansas law as a violation of free speech. The state tried to narrow its anti-BDS restrictions, but this, too, was overturned in July 2018.

Even though the courts are starting to rule on the right side on this, I’m bewildered that people face serious consequences for a BDS stance or refusing to give up their option of boycotting Israel. Shouldn’t any person have the choice whether to buy products from Israel or from companies that play a large role in Israel’s illegal settlements in occupied territory? How is this position viable in an America that prides itself on choice and freedom??

The White Moderate

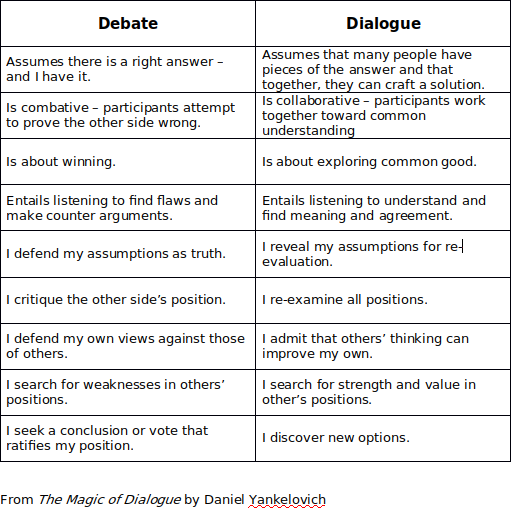

One of King’s more challenging statements is that white moderates and even liberals present more of a challenge to the liberation and economic emancipation of people of color than the KKK. This is because too often, white folks aren’t willing to personally risk anything to help change the rules that are stacked against people of color. Although there is white poverty and challenges for whites as well, the system isn’t systemically stacked against them the way it is for people of color or even for women. For many whites, this leads to a somewhat natural and understandable preference for order and calmness. But this has a dark side. This preference for order and calmness often means that many white folks – even with seemingly good intentions – oppose direct action and protest of injustice. All too often, this only leads to no change. The pot must be stirred, and discomfort is worth the price of change. After all, discomfort can lead to personal growth and a better understanding of the viewpoints of others.

I think of Jesus’ statement “Do not suppose that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I did not come to bring peace, but a sword” (Matthew 10:34). This statement stands out from the multitudes which establish his support for nonviolence, call him the prince of peace, and so forth. So what is going on here?

The verse comes from Matthew 10, where Jesus sends out the disciples to go and change the world. They are to announce that the kingdom of heaven is near and to “heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse those who have leprosy, and drive out demons.” The disciples are to go with minimal possessions, rely on the hospitality of those they meet in their journeys, and are not to judge or be angry at anyone who refuses them kindness or hospitality. Jesus says they will be like sheep among wolves and should be shrewd but also innocent as doves. They will be brought before the religious and national authorities and will be beaten. And they will even be betrayed by their own family members and by the family members of the friends and allies they make on their journeys. “When you are persecuted in one place, flee to another” (Matthew 10:23).

Jesus’ statement about the sword comes in this context of the disciples as a force for good in the world, confronting the evils of humanity and its systems. Everything related to the disciples and their actions is nonviolent. The verses immediately after (Matthew 10:35-39) explain what he means by the sword: he has come to turn a man against his father, a daughter against her mother, a daughter in law against her mother in law. He says that a man’s enemies will be the members of his own household, and that anyone who loves their father or mother more than Jesus is not worthy of him. “Whoever does not take up their cross and follow me is not worthy of me” (Matthew 10:39). Jesus is saying that his message of love, liberation, and justice is itself very controversial.

In a way, Jesus’ message stirs up violence, but only because it exposes the violence in our hearts, societies, and systems. This is also the cure if only we can face it and stick with it. So what Jesus means is that he is aware that his message divides and can stir up violent reactions, even though it’s absolutely clear that his followers are only to be innocent, peaceful, and kind.

While Martin Luther King, Jr. was in jail for his civil disobedience, he responded to critics who were against his policies of direct action, protest, and outspokenness about injustice. They wanted him to be quiet, to be patient, to let justice work itself out on its own slower pace. Just like Jesus, King responded that he had to speak out and that his message would indeed divide. This was necessary for goodness to increase.

I think this is part of why King considered himself a Christian. He understood Jesus’ message, applied it to his own day and time, and knew that this was a dangerous course of action. True nonviolence disturbs the status quo and puts a spotlight on injustice, racism, hatred, and nationalism. For many, it would feel more comfortable to ignore these and to simply accept the system as it is, hoping that change will come.

Jesus said that his message would divide families and that people should choose his message over family allegiance. Consider that today, a parallel to family is race. Ideally, we feel comfortable and safe with our family, and we look a lot like members of our family. In the same way, many of us often feel more comfortable around people of our own race and look somewhat similar to people of our own race, at least in terms of our skin color. But if Jesus’ message will disturb the comfort and peace of family, Jesus’ message will also disturb the comfort of staying within the perspectives of our own race and shying away from racial justice.

The word Nirvana means “extinction” and it means the eradication of all evil desires, of all passions, of all egotism, so that the flame of envy, hatred, and lust will have nothing to feed upon. This is the negative side of Nirvana.

The word Nirvana means “extinction” and it means the eradication of all evil desires, of all passions, of all egotism, so that the flame of envy, hatred, and lust will have nothing to feed upon. This is the negative side of Nirvana.